Or how I use dramatic light to create portraits and heritage images that tell a story.

There is always a moment, at the beginning of a photographic session, when everything falls into place: a shoulder turning slightly, a strand of hair tipping into shadow, the light catching just a fragment of cheek and letting the rest sink into an almost silent darkness.

That’s where my style begins.

It doesn’t appear out of nowhere. It has been nourished over the years by cinema, tenebrism, Rembrandt, Caravaggio, and by forgotten ruins and inhabited faces. By an obsession with telling stories with very little: a light, a body, a contrast, a past.

In this entry, I want to take you behind the scenes: where my photographic style comes from, what it actually looks like, and above all why it’s designed to serve you - artists, authors, freelancers, heritage institutions, museums and public bodies.

My Style in a Few Words: Cinematic, Dramatic Photography

If I had to sum up my style in a few lines, I would say:

A cinematic aesthetic: contrasted, narrative, inspired by films that sculpt light as if it were a character (for example: In the Mood for Love).

Dramatic lighting, close to tenebrism: large areas of shadow, targeted touches of light, deliberately intense.

A Rembrandt influence: a chiaroscuro treatment that sculpts faces or ruins and gives a sense of depth and gravity.

Arnaud de Montlivault, actor

Cinema as a First Matrix: Thinking in Scenes, Not “Poses”

A Cinematic Approach to Portraiture

Before I think in poses, I think in scenes.

The cinematic look is not just a “Netflix vibe” or a dark filter. For me, it means:

- Thinking in shots: intimate close-ups, wider contextual frames, full shots in a studio, workshop or historical site – like a storyboard.

- Using light as a narrative tool: not just lighting a face, but deciding exactly where the light falls to suggest doubt, strength, a crack, determination.

- Composing like in cinema: leading lines, meaningful backgrounds, coherent colours, depth.

When I create a professional portrait for a website, a book, a poster or a campaign, I’m not looking for a flattering “profile picture”.

I’m looking for the image that could be a still frame from a film in which you are the protagonist.

That’s why my portraits are often slightly dark rather than overexposed, built around a palette of deep earth tones (browns, greens, midnight blues, ochres), and designed to work as a series: for communication, a campaign, a press kit, an exhibition.

Nicolas, musician

The Rhythm of Cinema, Even in Historical Sites

In historical sites, the influence of cinema shows up differently:

I think in sequences: wide shots of the site, close details of textures, traces of time, then a scene with human presence (or intentional absence).

I aim to create an atmosphere, not just technical or educational documentation.

Each image tries to be the first or last scene of a story – and of History.

You don’t come to me just to get an “inventory”.

You come because you need a point of view, a universe. And that universe is deeply shaped by cinema and drama, without ever tipping into pathos.

Egypt, 2022

Tenebrism and Chiaroscuro: Learning to Speak the Language of Shadow

Tenebrism, originally, is a pictorial movement where shadow dominates and light seems to burst from within the scene. Historically, we think of Caravaggio and his followers. The Romantics, Rembrandt and other Dutch painters take chiaroscuro even further in subtlety.

In my practice, this becomes a series of very concrete choices:

- Embracing shadows: not trying to light everything, even with artificial light in the studio. Letting parts of the face fall away, suggesting more than showing.

- Creating emotional depth: a face partly in shadow acts as a metaphor. For example, showing strength while letting vulnerability be felt rather than displayed.

- Isolating the subject: in portraits as well as in my heritage series, dramatic light guides the eye straight to what matters.

In portrait work, this style is particularly effective for: artists and authors who want a strong, singular, non-standardised image; leaders and entrepreneurs who want to break away from interchangeable, ID-style corporate portraits; actors and performers who need atmospheric headshots that suggest a mood, a register, an intensity.

In heritage work, tenebrism gives:

- a sense of timelessness and sacredness to places (temples, ruins, sanctuaries);

- an almost intimate relationship with remains, millennia-old statues, inscriptions;

- a more emotional reading than a purely descriptive one – ideal for cultural mediation, exhibitions or publications.

Cambodia, 2016

Rembrandt: A Grammar for Sculpting Faces

The famous “Rembrandt lighting” every professional photographer knows – that small triangle of light on the cheek in the shadow – has almost become a cliché… except when it’s used with finesse.

What inspires me in Rembrandt is not only that triangle. It’s the way he respects faces, his ability to make a portrait intense yet calm, and that sense of honesty: faces are not perfect, but they are deeply alive.

On a shoot, this translates into light that is often:

- lateral, as if coming from a window;

- fairly soft, but very directional;

- designed to sculpt, not to flatten.

This kind of light is ideal for people who don’t like posing or feel “uncomfortable in front of the camera”.

Because the goal is not to transform you.

It’s to reveal you.

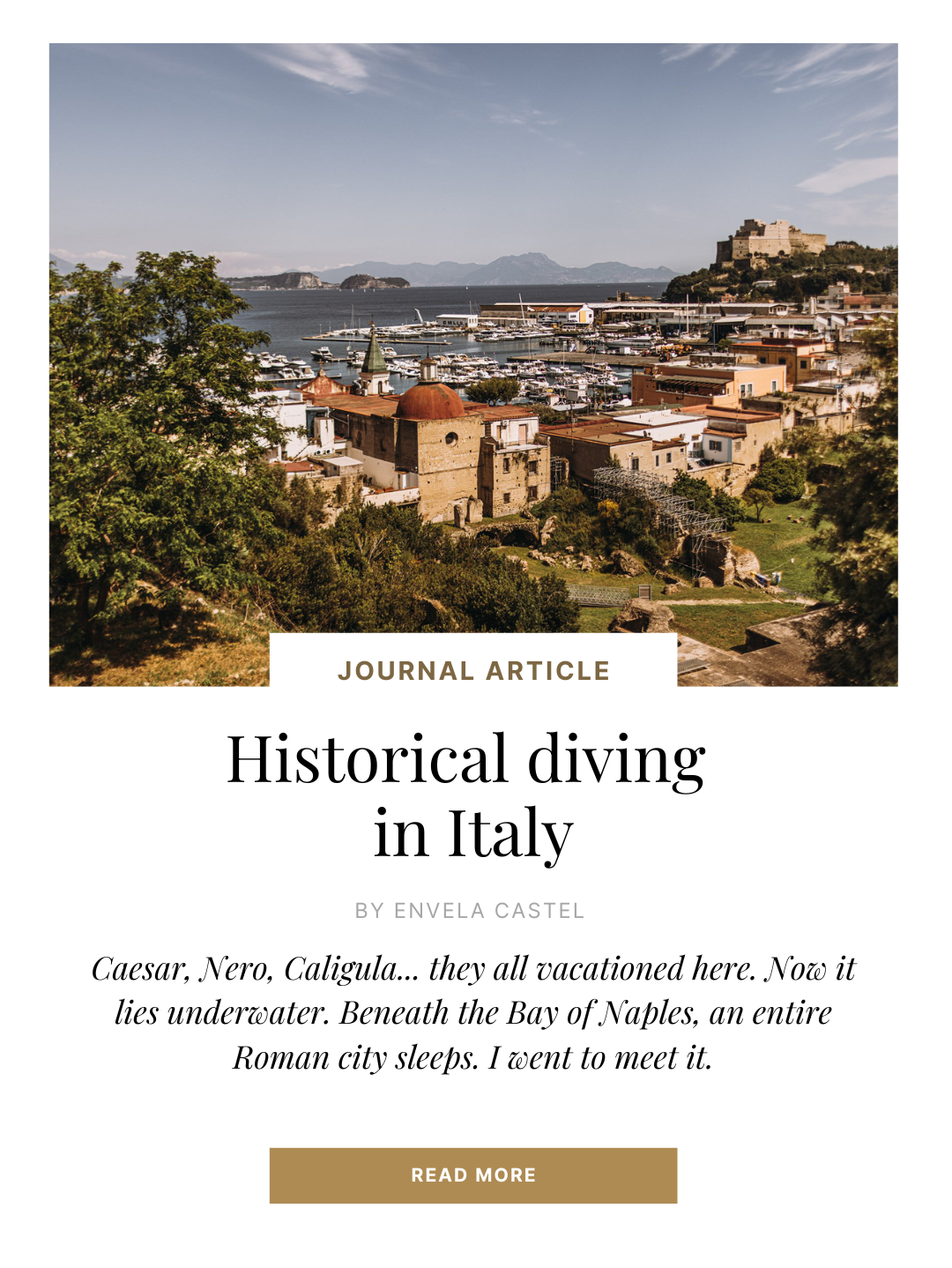

Places and Ruins: Heritage as a Character

Another major source of my style is historical sites and ruins.

When I photograph an ancient city or a forgotten fortification, I’m not documenting it like a technical survey. I’m trying to approach it as if the place were a character with memory, scars, and silence.

My approach combines:

- historical rigour, with a real concern for context and accuracy;

- a dramatic aesthetic, with chiaroscuro and deep tonalities. And sometimes, the light itself leaves me no choice – it really is that scarce.

For a local authority, museum, cultural institution or heritage organisation, this kind of imagery allows you to:

- showcase a site beyond the postcard image;

- build a distinctive visual identity;

- tell the story of a place as a living narrative, rather than a simple backdrop.

Egypt, 2022

Why This Style Can Serve Your Projects

Having a strong, marked style means refusing the “it-will-do” portrait – especially today, when everything looks Instagrammable and everything ends up looking the same.

I know it’s not for everyone. And that’s perfectly fine.

But if you need:

- images that actually say something about you without becoming needlessly theatrical;

- a strong visual universe for a book, an album, a theatre production, a brand strategy, a mediation campaign;

- a gaze that combines dramatic aesthetics and professional seriousness,

then this visual language becomes a powerful tool.

It allows you to:

- step out of the crowd of interchangeable portraits;

- assert a positioning, a mood, a sense of depth;

- leave a lasting image in the minds of those who encounter your work.

Conclusion: Showing Up as a Character, Not as a File

In the end, my photographic style comes from here:

- films that dare to embrace darkness;

- painters who respect the gravity of a face;

- ruins that remind us what time leaves behind.

All of this merges into a very concrete practice: cinematic, dramatic, inhabited portraits and heritage images.

You won’t be asked to “play a role”.

Instead, we simply make sure that, for a few moments, your light and your shadows tell what words can’t always express – with you as the main character.

Hélène Bernicot, Anne Le Goff, directors